Using X-ray technology to clear up an archeological secret

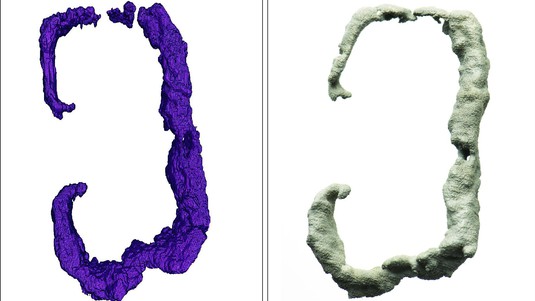

The chainmail shirt in 3D. © PIXE / EPFL

In an important first, EPFL and Vaud Canton’s archeology office used X-ray scanning technology to unlock the mysteries of an extremely rare chainmail shirt dating from Roman times. The results will go on display at the Cantonal Museum of Archeology and History in Lausanne from 26 April to 25 August.

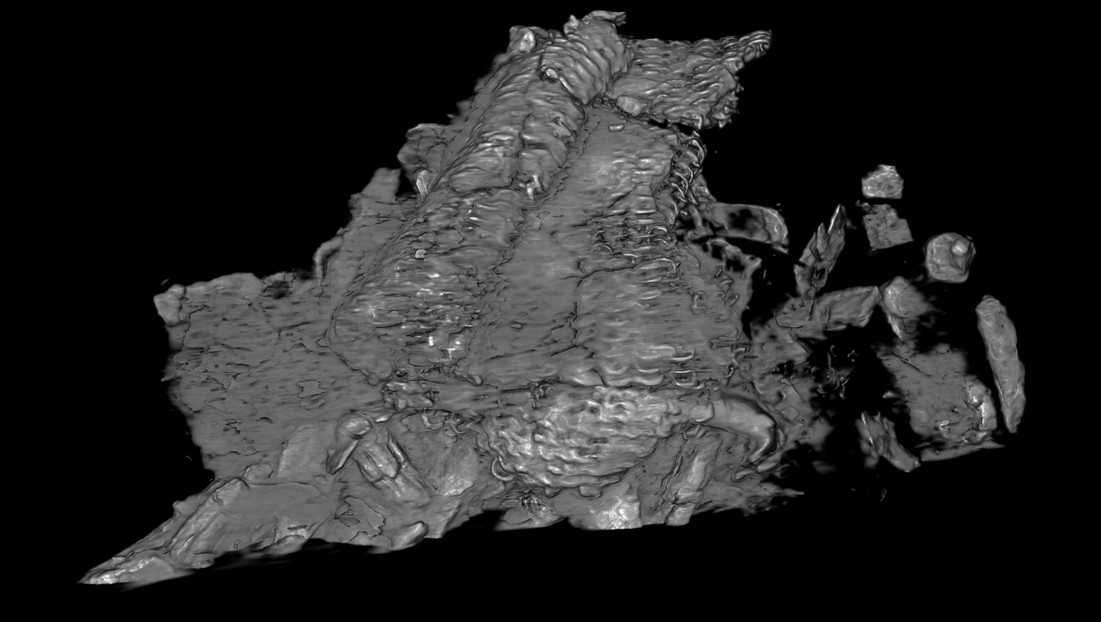

Researchers at EPFL have spent the past few months capturing 3D images of a Roman-era chainmail shirt using a computed tomography (CT) scanner. The piece of military armor, which dates back more than 2,000 years, is one of only a handful of similar items ever found in Europe. The twisted, corroded remains of the shirt were buried deep underground and fused with dozens of other objects that were almost impossible to tell apart using conventional investigatory techniques.

The EPFL researchers, working with Vaud Canton archeologists, then came up with a full inventory of items held within the chainmail shirt. Using a 3D printer, they reproduced the items while leaving the fragile shirt – reduced by the ravages of time to a hunk of distorted metal – completely intact. The findings will be unveiled in a special exhibition at the Cantonal Museum of Archeology and History from 26 April to 25 August 2019.

Pick apart and reconstruct

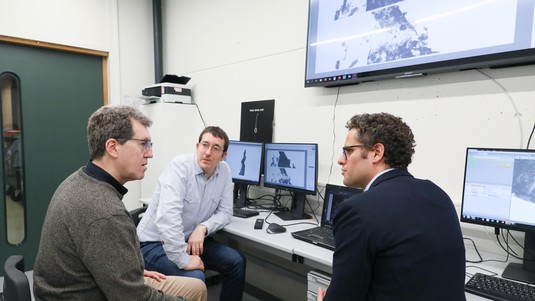

“This research shows the potential applications of CT scanning technology in archeology, where finds are often complex, deformed, distorted or fused,” says Pascal Turberg, who leads the ENAC Interdisciplinary Platform for X-ray micro-tomography (PIXE) at EPFL. “Using 3D imaging, we can pick these objects apart and reconstruct them.” The platform’s scanners can produce images down to a resolution of just 0.5 microns – extremely useful for working out the structure of the tiniest objects.

“The complex shape of the chainmail shirt made the whole process technically challenging,” adds Turberg. “What’s more, iron has a high X-ray attenuation coefficient and generates unwanted artefacts. Working on the fragment gave us a chance to hone our 3D imaging expertise. What we learned will serve us well in the future, allowing us to scan complex materials containing metallic elements.”

A staple, two brooches, and a handle pin

The findings proved just as exciting for the archeologists involved in the project. “This initiative was a success,” says Lionel Pernet, director of the Cantonal Museum of Archeology and History. “With 2D X-ray images, we could only see 30 or so complete items and fragments contained inside the shirt. The 3D scans revealed more than 160!” The newly discovered objects – all of which will go on display in 3D-printed form as part of the exhibition – include a furniture staple, two fibulas (Roman brooches with a spring-fastening mechanism), a cutting edge, and a pin for a cooking pot handle.

Building on success

The archeologists are already thinking about how CT scanning technology could enhance their research in the future. They’re planning to use the scanner to peer deep inside a remarkable toolkit unearthed at Vufflens-la-Ville, and to count the tree rings inside wooden posts and statues so they can date the pieces more accurately. “Scanning a funerary urn would save us a lot of time,” explains Matthieu Demierre, a lecturer at the University of Lausanne and an archeologist at Archeodunum, a firm that works with the cantonal archeology office. “Rather than working blind, we’d be able to see exactly where the bone fragments and other items are inside.”

- Collections printemps 2019. Actualité des découvertes archéologiques vaudoises.” Exhibition at the Cantonal Museum of Archeology and History, Lausanne, 26 April to 25 August 2019.